Bentham jeremy

,#44; или #x2c;

UTF-16

0x2C

URL-код

,

Запята́я (,) — знак препинания в русском и других языках. Иногда используется как десятичный разделитель.

Как знак препинания

В русском языке запятая используется на письме:

для обособления (выделения)

- определений, если определение находится после определяемого слова, либо имеет добавочное обстоятельственное значение, либо в случаях, когда определяемое слово является именем собственным или личным местоимением,

- обстоятельств, кроме тех случаев, когда обстоятельство является фразеологизмом; также в случаях, когда обстоятельство выражено существительным с предлогом (кроме предлогов невзирая на, несмотря на), запятая ставится факультативно;

также при использовании:

- причастных и деепричастных оборотов,

- обращений,

- уточнений,

- междометий,

- вводных слов (по некоторым источникам, вводные слова входят в состав обособленных обстоятельств, по другим — нет),

для разделения:

- между частями сложносочинённого, сложноподчинённого или сложного бессоюзного предложения;

- между прямой речью и косвенной, если косвенная речь стоит после прямой речи, а сама прямая речь не заканчивается знаками «!» и «?»; в этом случае после запятой (если она поставлена) всегда ставится тире.

- при однородных членах.

Как десятичный разделитель

В числовой записи, в зависимости от принятого в том или ином языке стандарта, запятой разделяются целая и дробная части либо разряды по три цифры между собой. В частности, в русском языке принято отделение дробной части запятой, а разрядов друг от друга пробелами; в английском языке принято отделение дробной части точкой, а разрядов друг от друга запятыми.

В информатике

В языках программирования запятая используется в основном при перечислении — например, аргументов функций, элементов массива.

Является разделителем в представлении табличных данных в текстовом формате CSV.

В Юникоде символ присутствует с самой первой версии в первом блоке Основная латиница (англ. Basic Latin) под кодом U 002C, совпадающим с кодом в ASCII.

На современных компьютерных клавиатурах запятую можно набрать двумя способами:

Запятая находится в нижнем регистре на клавише Del цифровой клавиатуры, если выбран русский региональный стандарт. Более правильно говорить, что в нижнем регистре на клавише Del цифровой клавиатуры находится десятичный разделитель для текущего регионального стандарта. Для США это будет точка. Запятая находится в верхнем регистре русской раскладки (набрать запятую можно лишь нажав клавишу ⇧ Shift. Существует мнение, что это неправильно, поскольку замедляет скорость набора текста (в русском языке запятая встречается чаще точки, для набора которой нажимать ⇧ Shift не требуется)[1].В культуре

- В детской считалочке:

Точка, точка, запятая —

Вышла рожица кривая,

Палка, палка, огуречик,

Получился человечек.

- В повести Лии Гераскиной «В стране невыученных уроков» Запятая является одной из подданных Глагола. Она описывается как горбатая старуха. Злится на Витю Перестукина за то, что тот постоянно ставит её не на место. В мультфильме «В стране невыученных уроков» Запятая также является подданной Глагола, но изображена иначе. Она выглядит не как старуха, а как девочка. Кроме того, она не такая злючка, хотя всё равно жалуется на то, что Витя ставит её не на место.

Варианты и производные

Средневековая, перевёрнутая и повышенная запятыеlink rel="mw-deduplicated-inline-style" href="mw-dаta:TemplateStyles:r130061706">Изображение

⹌⸴⸲Название

⹌: medieval comma

⸴: raised comma

⸲: turned comma

Юникод

⹌: U 2E4C

⸴: U 2E34

⸲: U 2E32

HTML-код

⹌: #11852; или #x2e4c;

⸴: #11828; или #x2e34;

⸲: #11826; или #x2e32;

UTF-16

⹌: 0x2E4C

⸴: 0x2E34

⸲: 0x2E32

URL-код

⹌: ⹌

⸴: ⸴

⸲: ⸲

В средневековых рукописях использовался ранний вариант запятой, выглядевший как точка с правым полукругом сверху. Для определённых сокращений использовался и знак повышенной запятой (⸴)[2].

В фонетической транскрипции Palaeotype для индикации назализации использовалась перевёрнутая запятая[3][4].

Все три символа закодированы в Юникоде в блоке Дополнительная пунктуация (англ. Supplemental Punctuation) под кодами U 2E4C, U 2E34 и U 2E32 соответственно.

См. также

.mw-parser-output .ts-Родственный_проект{background:#f8f9fa;border:1px solid #a2a9b1;clear:right;float:right;font-size:90%;margin:0 0 1em 1em;padding:.4em;max-width:19em;width:19em;line-height:1.5}.mw-parser-output .ts-Родственный_проект th,.mw-parser-output .ts-Родственный_проект td{padding:.2em 0;vertical-align:middle}.mw-parser-output .ts-Родственный_проект th td{padding-left:.4em}@media(max-width:719px){.mw-parser-output .ts-Родственный_проект{width:auto;margin-left:0;margin-right:0}}- Серийная запятая

- Точка

- Точка с запятой

- Число с плавающей запятой

Примечания

↑ Лебедев А. А. Ководство. § 105. Трагедия запятой. Студия Артемия Лебедева (14 июня 2004). Дата обращения: 17 мая 2019. Архивировано 12 декабря 2007 года. ↑ ichael Everson (editor), Peter Baker, Florian Grammel, Odd Einar Haugen. Proposal to add Medievalist punctuation characters to the UCS (англ.) (PDF) (25 января 2016). Дата обращения: 17 мая 2019. Архивировано 15 декабря 2017 года. ↑ Michael Everson. Proposal to encode six punctuation characters in the UCS (англ.) (PDF) (5 декабря 2009). Дата обращения: 17 мая 2019. Архивировано 7 апреля 2016 года. ↑ Simon Ager. Dialectal Paleotype (англ.) (htm). Omniglot. Дата обращения: 17 мая 2019.Ссылки

- , на сайте Scriptsource.org (англ.)

- ⹌ на сайте Scriptsource.org (англ.)

- ⸴ на сайте Scriptsource.org (англ.)

- ⸲ на сайте Scriptsource.org (англ.)

- Орфографические правила употребления запятой на gramota.ru

- Большая норвежская

- Брокгауза и Ефрона

- Britannica (онлайн)

- Britannica (онлайн)

- De Agostini

- Treccani

- BNF: 162295578

- SUDOC: 146880978

- Точка (.)

- Запятая (,)

- Точка с запятой (;)

- Двоеточие (:)

- Восклицательный знак (!)

- Вопросительный знакli>

- Многоточиеli>

- Дефис (‐)

- Дефис-минус (-)

- Неразрывный дефис (‑)

- Тиреli>

- Скобки ([ ], ( ), { }, ⟨ ⟩)

- Кавычки („ “, « », “ ”, ‘ ’, ‹ ›)

- Двойной вопросительный знакli>

- Двойной восклицательный знакli>

- Вопросительный и восклицательный знакli>

- Восклицательный и вопросительный знакli>

- Иронический знак (⸮)

- Интерробанг (‽)

- Предложенные Эрве Базеном (

,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  )

)

- Перевёрнутый восклицательный знак (¡)

- Перевёрнутый вопросительный знак (¿)

- Перевёрнутый интерробанг (⸘)

- Китайская и японская пунктуацияli>

- Паияннои (ฯ, ຯ, ។)

- Апатарц (՚)

- Шешт (՛)

- Бацаканчакан ншан (՜)

- Бут (՝)

- Харцакан ншан (՞)

- Патив (՟)

- Верджакет (։)

- Ентамна (֊)

- Колон (·)

- Гиподиастола (⸒)

- Коронис (⸎)

- Параграфос (⸏)

- Дипла (⸖)

- Гереш (׳)

- Гершаим (״)

- Нун хафуха (׆)

- Иоритэн (〽)

- Средневековая запятая (⹌)

- Повышенная запятая (⸴)

- Двойной дефис (⸗, ⹀)

- Двойное тире (⸺)

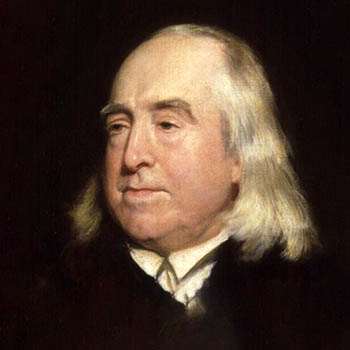

bentham jeremy

Jeremy Bentham was a British philosopher, social reformer, jurist, and human rights activist. Born on February 15, 1748, Bentham emerged as the founder of modern utilitarianism. He was a radical philosopher of law and politics, and gave ideas which were way ahead of his times.

Bentham’s theories laid the foundation of welfarism. He is one of the most important theorists in Anglo-American philosophy of law. Being a true humanitarian, he stood for the right of economic liberty, individual freedom, abolition of slavery, equality of women, freedom of expression, sexual liberty for homosexuals, and even animal rights. He also advocated the abolishment of physical punishment for children.

Bentham struggled in his life to give shape to his dream of creating an entirely utilitarian law code. He based the underlying principle of his ideal code of law on the philosophy of happiness; anything which creates greater happiness will decide between right and wrong.

This principle of greatest happiness forms the cornerstone of Bentham’s entire philosophy. By happiness he meant giving supremacy to pleasure over pain.

To test the amount of happiness, he classified between twelve kinds of pains and fourteen types of pleasures. This hedonistic theory of Bentham’s is often criticized for the utter disregard and ignorance towards the principle of justice and fairness.

His book, An Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislations presents his theories focusing on the principle of utility. According to Bentham, good is anything which causes least pain and greatest pleasure, and evil is what is most painful and least pleasurable. By these two feelings, he does not only mean physical but as well as spiritual kinds of pains and pleasures.

He also devised a criterion for the measurement of pains and pleasures; the criteria involved duration, intensity, proximity and certainty of the feeling among other factors.

Bentham advised the legislators not to create laws so unnecessarily strict that they may create more evil in society. The punishment for a crime should not be such that it may lead to more dangerous crimes and offenses, and thus to greater pain than pleasure in the society as a whole.

Bentham also gave economic principles leading to individual freedom. His work is considered to be one of the first attempts at a modern welfare economic system.

For Bentham, women rights were of utmost importance. In fact, he said that he chose to be a reformer only because of the grave indiscrimination against women he saw around him. He propagated complete equality between the two genders.

Bentham did not only stood for human rights, but he also took a stand for cruelty against animals. For him, presence of an intellect is not the criteria for fulfilling rights. Rather, the ability to suffer should be the benchmark when differentiating between acceptable and unacceptable treatment of a living being.

As a jurist, Bentham was the first person to have used the term ‘codify’. He strived for the codification of the common law in a proper, written set of statutes. He was the first advocate of codification of law in the United States and England.

Even though he wrote extensively on a myriad of topics in his lifetime, Bentham did not bring them to completion or before the public, except on rare occasions. His posthumous collection of writings reached to an estimated 30 million words, most of which is held by the UCL’s Special Collections.

Jeremy Bentham passed away on June 6, 1832. The world remembers him as an advocate of rights for all living beings, and the upholder of law and morality in grave times.

Buy books by Jeremy Bentham

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nineteenth century philosophy

(Modern Philosophy)

Name: Jeremy Bentham Birth: February 15, 1748 (Spitalfields, London, England) Death: June 6, 1832 (London, England) School/tradition: Utilitarianism Main interests Political Philosophy, Social Philosophy, Philosophy of Law, Ethics, economics Notable ideas greatest happiness principle Influences Influenced John Locke, David Hume, Baron de Montesquieu, Claude Adrien Helvétius John Stuart Mill

Jeremy Bentham (February 15, 1748 - June 6, 1832), jurist, philosopher, legal and social reformer, and English gentleman, is best known as an early advocate of utilitarianism. He was a political radical and a leading theorist for Anglo-American philosophy of law, and influenced the development of liberalism. Bentham was one of the most influential utilitarians, partially through his writings but particularly through his students all around the world, including James Mill, his secretary and collaborator on the utilitarian school of philosophy; James Mill's son, John Stuart Mill; a number of political leaders; Herbert Spencer; and Robert Owen, who later developed the idea of socialism.

Bentham argued in favor of individual and economic freedom, including the separation of church and state, freedom of expression, equal rights for women, animal rights, the end of slavery, the abolition of physical punishment (including that of children), the right to divorce, free trade, and no restrictions on interest rates. He supported inheritance tax, restrictions on monopoly power, pensions, and health insurance. Bentham also coined a number of terms used in contemporary economics, such as "international," "maximize," "minimize," and "codification."

Life

Bentham was born in 1748, in Spitalfields, London, into a wealthy Tory family. His father and grandfather were lawyers in the city of London, and his father intended for him to follow and surpass them as a practicing lawyer. Several stories illustrate his talents as a child prodigy: As a toddler, he was found sitting at his father's desk reading a multi-volume history of England; he was an avid reader, and began his study of Latin when he was three.

At Westminster School he won a reputation for writing Latin and Greek verse, and in 1760, his father sent him to Queen's College, Oxford, where he took his Bachelor's degree. In November of 1763, he entered Lincoln’s Inn to study law and took his seat as a student in the King’s Bench division of the High Court, where he listened with great interest to the judgments of Chief Justice Lord Mansfield. In December 1763, he heard Sir William Blackstone lecture at Oxford, but said that he detected the fallacies that underlay the grandiloquent language of the future judge.

He took his Master's degree in 1766. He was trained as a lawyer and was called to the bar in 1769, but spent more time performing chemistry experiments and speculating on the theoretical aspects of legal abuses than reading law books. He became deeply frustrated with the complexity of the English legal code, which he termed the "Demon of Chicane." On being called to the bar, he bitterly disappointed his father, who had confidently looked forward to seeing him become lord chancellor, by practicing law.

His first important publication, A Fragment on Government (1776), was a small part of his much larger Comment on the Commentaries of the jurist Blackstone, the classic statement of the conservative legal theory that was one of Bentham’s principal aversions. In 1785, Bentham traveled, by way of Italy and Constantinople, to Russia, to visit to his brother, Samuel Bentham, an engineer in the Russian armed forces; it was in Russia that he wrote his Defense of Usury (published 1785). Presented in the form of a series of letters from Russia, Bentham’s first essay on economics shows him to be a disciple of the economist Adam Smith, but one who argued that Smith did not follow the logic of his own principles. His main theoretical work, Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, appeared in 1780.

Bentham corresponded with many influential people. Adam Smith opposed free interest rates until Bentham's arguments on the subject convinced him otherwise. Because of his correspondence with Mirabeau and other leaders of the French Revolution, he was declared an honorary citizen of France, though later he strongly criticized the violence that arose when the Jacobins took power in 1792.

In 1791, Bentham published his proposal for a model prison building which he called the Panopticon, in which prisoners would be under continual observation by unseen guards. He approached both the French National Assembly and the British government about establishing such an institution, but the proposal was eventually abandoned. In 1813, however, the British Parliament voted to give him a large sum of money in compensation for his expenditures on the Panopticon scheme. Although the Panopticon was never built, the idea had an important influence on later generations of prison reformers.

After 1808, James Mill became Bentham’s disciple and began to help propagate his doctrine. His Catechism of Parliamentary Reform, written in 1809, was published in 1817. Chrerstomathia, a series of papers on education, appeared in 1816, and in the following year, James Mill published his edition of Bentham’s Table of the Springs of Action, an analysis of various pains and pleasures as incentives for action.

In 1823, Bentham and John Stuart Mill co-founded the Westminster Review as a journal for philosophical radicals.

Jeremy Bentham's Auto-Icon in University College London

Jeremy Bentham's Auto-Icon in University College London

Bentham is frequently associated with the foundation of the University of London, specifically University College London, though in fact he was seventy-eight years old when it opened in 1826, and played no active part in its establishment. However, he strongly believed that education should be more widely available, particularly to those who were not wealthy or who did not belong to the established church, both of which were required of students by Oxford and Cambridge. As University College London was the first English university to admit all, regardless of race, creed, or political belief, it was largely consistent with Bentham's vision, and he oversaw the appointment of one of his pupils, John Austin, as the first Professor of Jurisprudence in 1829. It is likely that without his inspiration, University College London would not have been created when it was. On his death, Bentham left the school a large endowment.

As requested in Bentham’s will, his body was preserved and stored in a wooden cabinet, termed his "Auto-Icon," at University College London. It has occasionally been brought out of storage for meetings of the Council (at which Bentham is listed on the roll as "present but not voting") and at official functions so that his eccentric presence can live on. The Auto-Icon has always had a wax head, as Bentham's head was badly damaged in the preservation process. The real head was displayed in the same case for many years, but became the target of repeated student pranks including being stolen on more than one occasion. It is now securely locked away.

There is a plaque on Queen Anne's Gate, Westminster, commemorating the house where Bentham lived, which at the time was called Queen's Square Place.

Thought and works

Did you know?

Jeremy Bentham, jurist, philosopher, legal and social reformer, and English gentleman, is regarded as the founder of modern UtilitarianismJeremy Bentham exercised considerable influence on political reform in England and on the European continent. His ideas are evident in a number of political reforms, including the Reform Bill of 1832, and the introduction of the secret ballot. He devoted a considerable amount of his time to various projects involving social and legal reforms, and is said to have often spent eight to twelve hours writing every day. On his death he left tens of thousands of pages and outlines of unpublished writing, which he hoped others would organize and edit. (The Bentham Project, set up in the early 1960s at University College, is working on the publication of a definitive, scholarly edition of Bentham's works and correspondence.)

Bentham believed that many social and political ills in England were due to an antiquated legal system, and to the fact that economy was in the hands of a hereditary landed gentry which resisted modernization. He rejected many of the concepts of traditional political philosophy, such as “natural rights,” state of nature, and “social contract,” and worked to construct positive alternatives. He emphasized the use of reason over custom and tradition in legal matters, and insisted on clarity and the use of precise terminology. Many traditional legal terms, he said, such as “power,” “possession,” and “right,” were “legal fictions” which should be eliminated or replaced with terminology more appropriate to the specific circumstances in which they were to be used.

Works

In 1776, Bentham anonymously published his Fragment on Government, a criticism of Blackstone's Commentaries, disagreeing, among other things, with Blackstone's espousal of natural rights. Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation was published in 1780. Other works included, Panopticon, in which he suggested improvements in prison discipline, Discourse on Civil and Penal Legislation (1802), Punishments and Rewards (1811), Parliamentary Reform Catechism (1817), and A Treatise on Judicial Evidence (1825).

John Bowring, a British politician who had been Bentham's trusted friend, was appointed his literary executor and charged with the task of preparing a collected edition of his works. This appeared in eleven volumes in 1843.

Rights and Laws

Bentham defined liberty as “freedom from restraint.” He rejected the traditional concept that “natural law,” or “natural rights,” existed, saying that there was no time when people did not exist within a society and did not have some kind of restrictions imposed on them. He defined law as simply a command expressing the will of a sovereign, and rights as created by law. Laws and rights could not exist without government to enforce them. If there were a “right” which everyone exercised freely, without any kind of restraint, anarchy would result. These ideas were especially developed in his Anarchical Fallacies (a criticism of the declarations of rights issued in France during the French Revolution, written between 1791 and 1795, but not published until 1816, in French).

Bentham recognized that laws were necessary to maintain social order and well-being, and that law and government could play a positive role in society. Good government required good laws, and a government chosen by the people which created laws to protect their economic and personal goods was in the interest of the individual.

Utilitarianism

Bentham is the first and perhaps the greatest of the "philosophical radicals"; not only did he propose many legal and social reforms, but he also devised moral principles on which they should be based. His idea of Utilitarianism was based on the concept of psychological hedonism, the idea that pleasure and pain were the motivation for all human action, and psychological egoism, the view that every individual exhibits a natural, rational self-interest. Bentham argued that the right act or policy was that which would cause "the greatest happiness for the greatest number." This phrase is often attributed to Bentham, but he credited Joseph Priestley for the idea of the greatest happiness principle: "Priestley was the first (unless it was Beccaria) who taught my lips to pronounce this sacred truth: That the greatest happiness of the greatest number is the foundation of morals and legislation."[1]

Bentham also suggested a procedure to mechanically assess the moral status of any action, which he called the "Hedonic calculus" or "felicific calculus." Utilitarianism was revised and expanded by Bentham's student, John Stuart Mill. In Mill's hands, "Benthamism" became a major element in the liberal conception of state policy objectives.

It is often said that Bentham's theory, unlike Mill's, lacks a principle of fairness embodied in its conception of justice. Thus, some critics object, it would be moral, for example, to torture one person if this would produce an amount of happiness in other people outweighing the unhappiness of the tortured individual. However, Bentham assigned to law the role of defining inviolable rights which would protect the well-being of the individual. Rights protected by law provide security, a precondition for the formation of expectations. As the hedonic calculus shows "expectation utilities" to be much higher than natural ones, it follows that Bentham did not favor the sacrifice of a few to the benefit of the many.

Bentham’s perspectives on monetary economics were different from those of Ricardo. Bentham focused on monetary expansion as a means to full employment. He was also aware of the relevance of forced saving, propensity to consume, the saving-investment relationship and other matters which form the content of modern income and employment analysis. His monetary view was close to the fundamental concepts employed in his model of utilitarian decision making. Bentham stated that pleasures and pains can be ranked according to their value or “dimension” such as intensity, duration, and certainty of a pleasure or a pain. He was concerned with maxima and minima of pleasures and pains, and they set a precedent for the future employment of the maximization principle in the economics of the consumer, the firm and in the search for an optimum in welfare economics.

Major Works

- Bentham, Jeremy. A Comment on the Commentaries. 1974. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0199553471

- Bentham, Jeremy. Fragment on Government. 1776. Oxford University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0199553471

- Bentham, Jeremy. Introduction to Principles of Morals and Legislation. 1780. British Library, Historical Print Editions, 2011. ISBN 978-1241475611

- Bentham, Jeremy. Of the Limits of the Penal Branch of Jurisprudence . 1782. Oxford University Press, 2010. ISBN 978-0199570737

- Bentham, Jeremy. Panopticon. 1785. Verso, 2011. ISBN 978-1844676668

- Bentham, Jeremy. Defence of Usury. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2004. ISBN 978-1419115509

- Bentham, Jeremy. Parliamentary Reform Catechism. 1817. Kessinger Publishing, LLC, 2010. ISBN 978-1166617318

- Bentham, Jeremy. A Treatise on Judicial Evidence. 1825. Nabu Press, 2010. ISBN 978-1144626646

- Bentham, Jeremy. The Rationale of Reward. 1825. Nabu Press, 2012. ISBN 978-1276823883

- Bentham, Jeremy. The Rationale of Punishment. 1830. Prometheus Books, 2009. ISBN 978-1591026273

Notes

↑ Jeremy Bentham, The Works of Jeremy Bentham: Published under the Superintendence of His Executor, John Bowring, Vol X, (Adamant Media Corporation, 2001, ISBN 978-1402163838), 142.References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bentham, Jeremy. The Works of Jeremy Bentham: Published under the Superintendence of His Executor, John Bowring, Vol X. Adamant Media Corporation, 2001. ISBN 978-1402163838

- Halévy, Elie. La formation du radicalisme philosophique, 3 vols. Paris, 1904 [The Growth of Philosophic Radicalism. Tr. Mary Morris. London: Faber Faber, 1928.]

- Harrison, Ross. Bentham. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1983. ISBN 978-0415203623

- Hart, H.L.A. "Bentham on Legal Rights." In Oxford Essays in Jurisprudence. Oxford: The Clarendon Press, 1973. ISBN 978-0198253136

- MacCunn, John. Six Radical Thinkers. Arno Press, 1979. ISBN 978-0405117206

- Mack, Mary Peter. Jeremy Bentham: An Odyssey of Ideas 1748-1792. London: Heinemann, 1962. ASIN B000JLDCFK

- Manning, D.J. The Mind of Jeremy Bentham. London: Longmans, 1968. ISBN 978-0313225796

- Plamenatz, John. The English Utilitarians. Oxford: Oxford Unversity Press, 1949.

- Robinson, Dave and Judy Groves. Introducing Political Philosophy. Icon Books, 2003. ISBN 184046450X

- Rothbard, Murray N. Classical Economics: An Austrian Perspective on the History of Economic Thought. Edward Elgar Publishing, 1995. ISBN 185278962X

- Stephen, Leslie. The English Utilitarians. London: Duckworth, 1900. ASIN B002B7I8L8

External links

All links retrieved July 31, 2022.

General philosophy sources

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

Jeremy Bentham was born in 1748 to a wealthy family. A child prodigy, his father sent him to study at Queen’s College, Oxford University, aged 12. Although he never practiced, Bentham trained as a lawyer and wrote extensively on law and legal reform. He died in 1832 at the age of 84 and requested his body and head to be preserved for scientific research. They are currently on display at University College London.

Jeremy Bentham is often regarded as the founder of classical utilitarianism. According to Bentham himself, it was in 1769 he came upon “the principle of utility”, inspired by the writings of Hume, Priestley, Helvétius and Beccaria. This is the principle at the foundation of utilitarian ethics, as it states that any action is right insofar as it increases happiness, and wrong insofar as it increases pain. For Bentham, happiness simply meant pleasure and the absence of pain and could be quantified according to its intensity and duration. Famously, he rejected the idea of inalienable natural rights—rights that exist independent of their enforcement by any government—as “nonsense on stilts”. Instead, the application of the principle of utility to law and government guided Bentham’s views on legal rights. During his lifetime, he attempted to create a “utilitarian pannomion”—a complete body of law based on the utility principle. He enjoyed several modest successes in law reform during his lifetime (as early as 1843, the Scottish historian John Hill Burton was able to trace twenty-six legal reforms to Bentham’s arguments) and continued to exercise considerable influence on British public life.

Many of Bentham’s views were considered radical in Georgian and Victorian Britain. His manuscripts on homosexuality were so liberal that his editor hid them from the public after his death. Underlying his position on the decriminalization of homosexuality were his beliefs that the right end of government is the maximization of happiness, and that the severity of punishment should be proportional to the harm inflicted by the crime. He was also an early advocate of animal welfare, famously stating that their capacity to feel suffering gives us reason to care for their well-being: “The question is not can they reason? Nor, can they talk? But can they suffer?”. As well as animal welfare and the decriminalization of homosexuality, Bentham supported women’s rights (including the right to divorce), the abolition of slavery, the abolition of capital punishment, the abolition of corporal punishment, prison reform and economic liberalization.

Bentham also applied the principle of utility to the reform of political institutions. Believing that with greater education, people can more accurately discern their long-term interests, and seeing progress in education within his own society, he supported democratic reforms such as the extension of the suffrage. He also advocated for greater freedom of speech, transparency and publicity of officials as accountability mechanisms. A committed atheist, he argued in favor of the separation of church and state.

How to Cite This Page

Hampton, L. (2023). Jeremy Bentham. In R.Y. Chappell, D. Meissner, and W. MacAskill (eds.), An Introduction to Utilitarianism , accessed .

Want to learn more about utilitarianism?

Representative Works of Jeremy Bentham

Resources on Jeremy Bentham’s Life and Work

- Who was Jeremy Bentham? The Bentham Project, University College London.

- Crimmins, J. E. (2019). Jeremy Bentham. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Zalta, E. N. (ed.).

- Sweet, W. Jeremy Bentham. The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Schofield, P. (2012). Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism. Philosophy Bites Podcast.

- Gustafsson, J. E. (2018). “Bentham’s Binary Form of Maximizing Utilitarianism”, British Journal for the History of Philosophy, 26 (1): 87–109.

Prominent Quotes of Jeremy Bentham

- “[T]he dictates of utility are just the dictates of the most extensive and enlightened—i.e.well-advised—benevolence”.

- “The principle of utility judges any action to be right by the tendency it appears to have to augment or diminish the happiness of the party whose interests are in question.”

- “Create all the happiness you are able to create: remove all the misery you are able to remove. Every day will allow you to add something to the pleasure of others, or to diminish something of their pains.” (Bentham’s advice to a young girl, 1830)

- “The day may come when the non-human part of the animal creation will acquire the rights that never could have been withheld from them except by the hand of tyranny. The French have already discovered that the blackness of the skin is no reason why a human being should be abandoned without redress to the whims of a tormentor. Perhaps it will some day be recognised that the number of legs, the hairiness of the skin, or the possession of a tail, are equally insufficient reasons for abandoning to the same fate a creature that can feel? What else could be used to draw the line? Is it the faculty of reason or the possession of language? But a full-grown horse or dog is incomparably more rational and conversable than an infant of a day, or a week, or even a month old. Even if that were not so, what difference would that make? The question is not Can they reason? Or Can they talk? but Can they suffer.”